by Katherine Garvey ✎

This past growing season, Baltimore saw an abnormal number of sudden, heavy rainfall events. These occurrences were not isolated, of course. Massive downpours overwhelmed many parts of the country over the past several months. In Maryland, our cities are similarly suffering—Annapolis floods regularly, Old Ellicott City has survived several “once-in-a-lifetime” storms within just the past decade, and areas of Baltimore City are being slowly eaten away by increasing water levels.

For Baltimore, our subdivisions, streets, and homes are particularly vulnerable. Aging, patchwork infrastructure, and the fact that said infrastructure was never designed with climate change in mind, has resulted in inadequate stormwater management for many neighborhoods. The result of that mismanaged stormwater in combination with the aforementioned modern, supercharged rainstorms often results in standing water. Standing water, in turn, threatens foundations, erodes sidewalks, drowns ornamental gardens, and invites the guest no one wants: mosquitoes. The good news is that native plants can help to alleviate many of these flooding and drainage problems.

Rain Gardens and Native Plants

Typical turf grass and ornamental plants have shallow root systems. They did not evolve with our soils or critters, and therefore prefer to stay in the top several inches to absorb the easiest available nutrients, free of pests. Native plants, on the other hand, have root systems that are incredibly diverse and, most often, deep. Little bluestem, for example, has roots reaching to almost six feet deep, while plants such as heath aster have roots as deep as nine feet! These roots act as pathways for water to easily travel down into the earth, while the roots themselves draw up and utilize excess water. As that water evaporates over time, rather than running off into the nearest storm drain, the properties of evaporation take hold. As moisture rises from the soil, it lowers the surrounding temperature. To put a crowning jewel on these benefits: less standing water means fewer nurseries for mosquitoes.

Maryland homeowners and other stewards of land can exponentially improve these benefits by installing native plants as part of a rain garden. The really exciting part? The concept of modern rain garden design also evolved right here in Maryland, just like our native plants!

Maryland: The Birthplace of Rain Gardens

In the early 1990’s, Dick Brinker, a housing developer building a 199-home subdivision in Prince George’s County Maryland, approached Larry Coffman, then the County Associate Director for Programs and Planning in the Department of Environmental resources. He sought to replace the historical, expensive way to manage stormwater since the project was over budget. The pair, alongside Brinker’s daughter, Theresa, the then-president of the TABCO land development company, redesigned the entire neighborhood to include small bioretention gardens on each lot. The result was, literally and figuratively, groundbreaking. The developer was able to save costs, add value to the homes, and lessen the environmental impact on the entire area. Those “bioretention gardens” were rebranded as “rain gardens,” and the rest is history (Coffman, 1995, pp. 5–7). Prince George’s County began sharing manuals for the installation of residential rain gardens, and local planners across the country took notice.

The results were so successful that the EPA later published a factsheet citing the Prince George’s County manual as its primary source, lauding the benefits of rain gardens to provide “water treatment that enhances the quality of downstream water bodies,” and that such gardens “provide shade and wind breaks, absorb noise,” and are overall just wonderful to look at (EPA, 1999, p. 2).

Important Acknowledgement: Water wisdom is ancient. Although Prince George’s County popularized modern rain gardens in the 1990’s, Indigenous communities worldwide have been shaping land to live with water for thousands of years. Today’s rain gardens continue that tradition of honoring and working with nature.

Best Natives for Baltimore Rain Gardens & Wet Areas

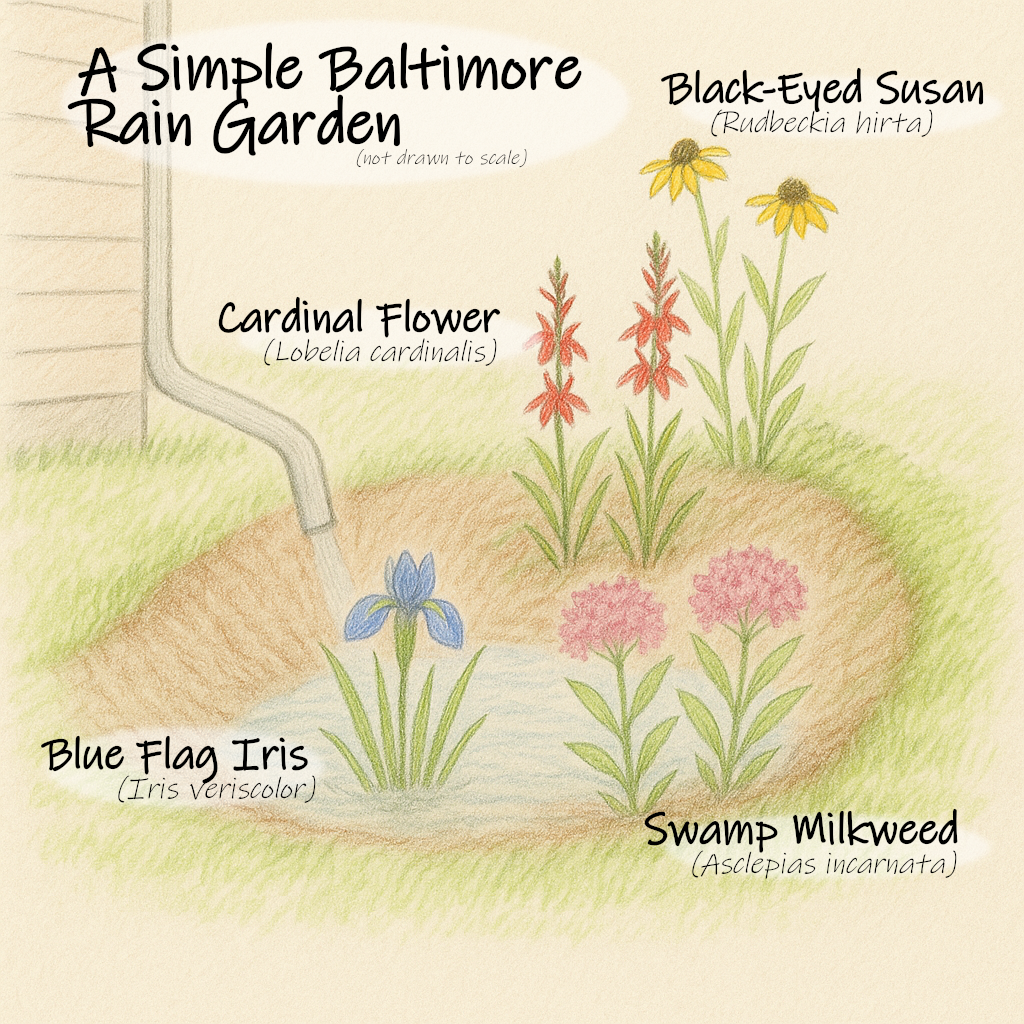

If you are one of the many in the Baltimore area that suffer from drainage problems, consider installing a rain garden with native plants as the helpers. Soggy spots of the yard (think one that squishes when you walk through it!) or corners that seem to flood with every storm, you have options! Here are some excellent choices for wet or periodically flooded soils:

- Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata): Beloved by the beautiful and charismatic monarchs; thrives in wet soil.

- Blue Flag Iris (Iris veriscolor): Striking blooms; very happy with wet feet; excellent for rain gardens.

- Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis): Brilliant red spikes that hummingbirds can’t resist.

- New York Ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis): Tall, purple-flowering, late-season pollinator magnet.

- Soft Rush (Juncus effusus): Adds texture and handles standing water like a champ.

- River Birch (Betula nigra): A beautiful, fast-growing tree with peeling bark that loves wet feet that would do in sizable rain gardens. Can grow large (upwards of seventy feet), and should not be placed where it may intrude on home foundations. Note: Straight species River Birches are exceptionally tall. However, there are naturally occurring variants of this species that are substantially smaller, such as “Little King” which would be far more reasonable for small Baltimore City lots while still providing the same resources for rain gardens and local wildlife!

Designing a Rain Garden: Think Like a Sponge

When planting for drainage, it helps to imagine your yard as a dry sponge. The goal is to slow water down, spread it out, and let it soak in. Rain gardens are often planted in low spots or at the end of downspouts (at least ten feet away from a building’s foundation). The gardens themselves are essentially depressions in the ground, typically six to twelve inches deep, where water can collect, with a low berm on the downslope side. The downslope berm helps to keep water within the rain garden basin even during heavy storms and allow it to soak into the ground.

Plants that enjoy having wet feet should be planted at the bottom of the basin, with moisture-tolerant plants planted on the sloping sides. At the upper edges, or “rim,” use plants that prefer to be kept dry and define the boundary of the garden. Large natives like River Birch (even its smaller version!) should only be used in more sizable rain gardens. These native giants, when paired with pollinator-friendly perennials, create a functional, beautiful planting.

Maryland’s Legacy

From Prince George’s County’s pioneering work in the 1990’s to the countless Indigenous practices of water stewardship across the globe, rain gardens remind us that we thrive when we design with nature, not against it. Here in Baltimore and the surrounding counties, where aging infrastructure strains under climate-driven storms, every yard planted with natives becomes part of the solution. By carving out a basin, thinking like a sponge, and filling that space with deep-rooted, native plants, you are storm-proofing your property, reducing mosquito habitat, and creating a haven for pollinators and birds.

Maryland was the birthplace of modern rain gardens, and it can also be the place where everyday homeowners and land stewards lead the way by living with water wisely. A single rain garden may not stop a city from flooding, but dozens stitched together may save a street. Rain gardens in every lot, hundreds across the city, would change the story.

So the next time the skies open up over Baltimore, and it will, imagine the rain sinking into your soil instead of rushing away. Imagine a yard that buzzes with pollinators, shelters songbirds, and stays resilient no matter the storm. That future starts with a shovel, a few native plants, and the will to reimagine what our backyards can do.

To become a Wild Ones member, or give the gift of membership, visit our national site, WildOnes.org. You can also make a donation to Wild Ones Greater Baltimore here. ❀

References

Coffman, L. (1995, August/September). Maryland developer grows “rain gardens” to control residential runoff. Nonpoint Source: News-Notes, (42), 5–6.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (1999, September). Storm water technology fact sheet: Bioretention (EPA 832-F-99-012). Office of Water. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=200044BE.txt.